Okay, so the thing I find super cool about the pictures that inspired Mussorgsky’s composition is that they were mostly related to other works of art. Viktor Hartmann was an architect and designer in addition to being a painter, and many of his works in the exhibit were designs for costumes, buildings, or architectural studies during his travels abroad.

I like how it shows this massive network of inspiration behind art. What had led to Mussorgsky’s best known work was not merely a picture hanging in a gallery, but author of a short story, which inspired a ballet to be made, which needed a unique costume designer, and on and on. I guess I just really like how everything is connected, that creativity is constantly giving birth, and nothing exists in a vacuum.

Anyway, the paintings. Unfortunately, most of the 400+ works of Hartmann’s retrospective were lost, and we will never know some of the images that correspond to the movements in Mussorgsky’s suite. We do however have the descriptions by Stasov, who had organized the exhibition and also was the dedictee of Mussorgsky’s work.

The watercolors and sketches that we know Mussorgsky used were:

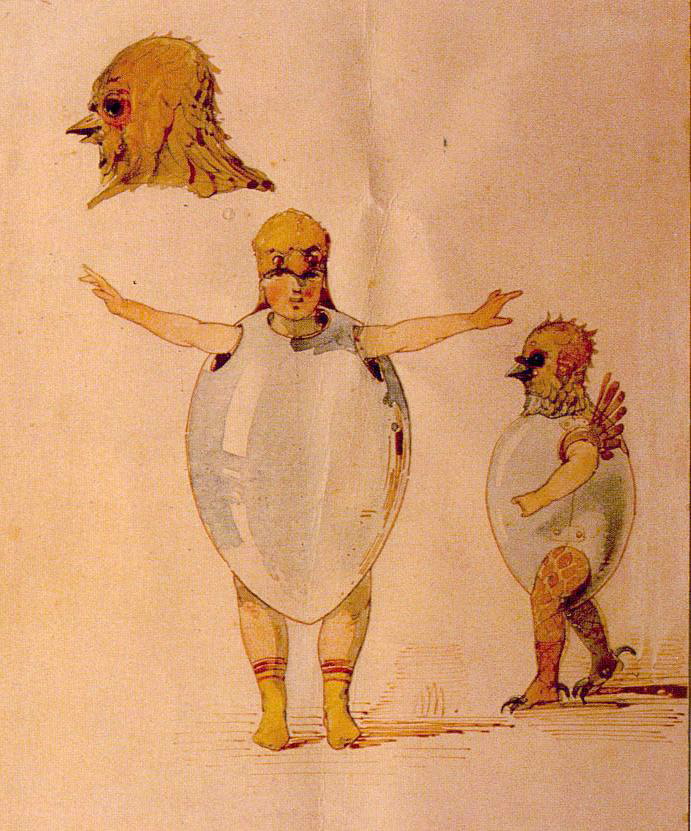

5. Ballet of the Chicks in their Shells

Hartmann made 17 sketches for the Ballet “Trilby”, which was based on the short story by French author Charles Nodier. The ballet featured the children of the Imperial Ballet School, and costumes were designed for them to look like butterflies, birds, and unhatched chicks.

6. Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle (Two Polish Jews: one rich, the other poor)

These were based on two paintings, both which Mussorgsky owned and had lent to the retrospective.

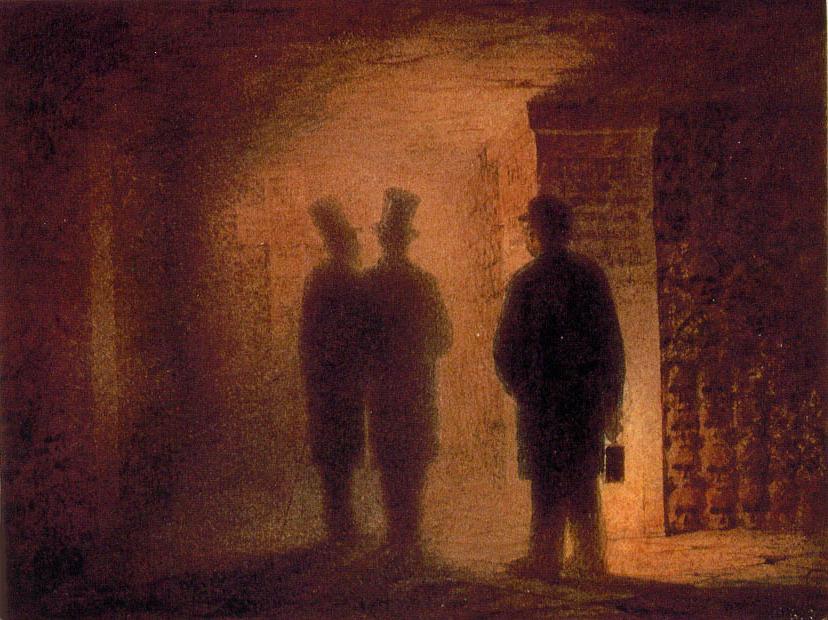

8. Catacombs

After graduating the Academy of Fine Arts with distinction, Hartmann was given the privilege of continuing his studies abroad for four years, three of which he spent in France. This painting is a self portrait of sorts, showing him and a fellow architect descending into the burial grounds. Yes, that is a wall of skulls. You almost don’t notice it initially. The Europeans really knew how to re-purpose everything.

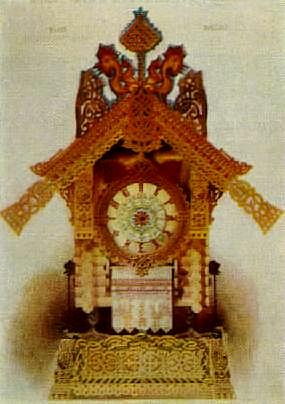

9. The Hut on Fowl’s Legs

To me, this painting is not nearly as terrifying as the music or supernatural creature that it was based on. I mean, Baba Yaga is a witch that flies around on a mortar and eats children. Hartmann’s design for a clock is a portrayal of her hut in the depths of the woods, which is built on chicken legs.

(So many questions. Like, is the mortar broom-sized? Can you imagine what kind of killing instrument it would be if it were broom sized? And are the chicken legs alive? Like, can the hut suddenly scrabble away if angry villagers come by?)

The artist was fascinated by the character of Baba Yaga. He once went disguised as her to a costume ball, where everyone else was dressed as foreign characters, either monks or creatures of classical mythology. Stasov recalls that Hartmann shocked everyone by coming as the deformed witch:

“…along rows of plaster of Paris Greek gods and goddesses, a witch, Baba Yaga, was running, her red braids streaming out behind her. A big fuzzy hat was pulled down over her eyes, her feet were wrapped in cloth, bony arms stuck out of the sleeves of her robe, a sparse beard protruded from her chin, her horrible eyes gleamed maliciously on her painted face, tusks stuck out of her half-opened mouth.”

Mussorgsky incorporated into the music the tolling of the clock, and the whirling terror of the witch chasing after children. Similar in grotesqueness to the Gnome, the structural placement of Baba Yaga gives symmetry to the suite, as it screeches pellmell into the redeeming glory of the concluding movement.

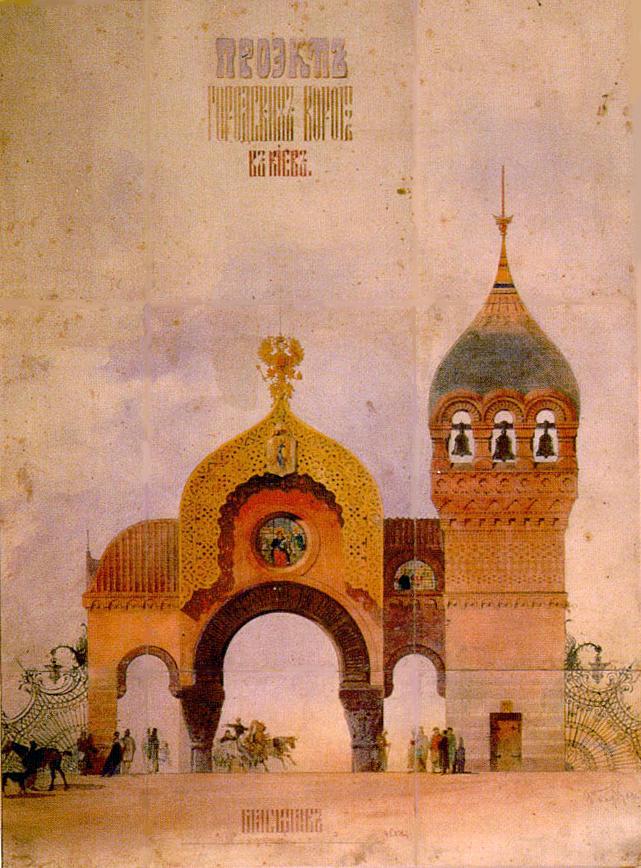

10. The Great Gate of Kiev

Hartmann considered the Great Gate of Kiev to be his best work. Tsar Alexander II had held a competition for the design of a great gate to commemorate his survival of the assasination attempt on him in 1866, but the project was cancelled. Maybe the Tsar was kind of squeamish about publicly remembering his own murder plot.

A word on some of the others:

1. Gnome

According to the story line of the piece, after the larger than life Mussorgsky announces himself at the gallery, he is startled by one of Hartmann’s designs for a wooden nutcracker, in the form of a gnome with large teeth. There is no image to this one, but Stasov said that it was both ” a design for a carved wooden nutcracker apparently in the form of a gnome” and that it was “clumsily running with crooked legs.” Mussorgsky depicts the crooked legs by constantly changing groupings from 2 to 3, changing meter, lurches of forzandi, scampering rapid outbursts that cut off abruptly, and menacing intervals. It kind of reminds me of a stop-action horror movie, with a big mechanical spider that comes to life, making this awful whirring clack clack clack noise as the grotesque legs multiply rapidly and fill your vision and ugh, heebie jeebies.

2. The Old Castle

Stasov describes the image as ““A medieval castle before which a troubadour sings a song”. A boat may have been involved. The movement is very bacarolle-y. Or wait, the painting was a WATER-color….

I can see you rolling your eyes. Don’t think I can’t see you.

3. Tuileries (The Tuileries Gardens: Children’s Quarrel After A Game).

Many of the sketches of the exhibition were from Hartmann’s travels. Stasov reported that the painting was of “An avenue in the garden of the Tuileries, with a swarm of children and nurses”. This was the garden near the Louvre in Paris, and Hartmann had probably painted in children being rambunctious in the garden for scale.

7. This drawing had shown a group of market women “quarreling violently” by their pushcarts, which of course Mussorgsky tried to imagine. In the margins of his score he scribbled

“Great news! M. de Puissangeout has just recovered his cow, The Fugitive. But the good crones of Limoges are not entirely agreed about this, whereas M. be Panta-Pantaleon’s nose, which is in the way, remains the colour of a peony”.

He had crossed this out, along with an earlier attempt, which is too bad. I really would like to know if the alcoholic nose has anything to do with the vicious fight.